Detroit Sound Conservancy participated in this roundtable discussion on preserving Detroit’s Black history organized by Noir Design Parti.

Overview

What are the conversations we need to have now so that Detroit’s descendants no longer have to solve the same problems that plague our communities today?

A half-century after the 1967 uprising/rebellion, black historians often still feel out of place in the archive world. Our discussion, hosted Noir Design Parti, is looking at helping to identify concerns, identify collection resources for Black history archives, and promote the needs of archivists/ historians and archives from people of color and the places important to their history. There will be a short introductory presentation and round table discussions by historians and archivists of Detroit’s leading historical projects and collections.

Paige Watkins, Black Bottom Archives

Carleton S. Gholz, Detroit Sound Conservancy

Ruth Mills, Quinn Evans Architects

David Head and Karen Hudson Samuels, Detroit Historical Society’s Black Historic Sites Committee

Carl Nielbock, CAN Art Handworks

Original Facebook event page here.

Introductions

Saundra Little: We’re going to start out the panel by allowing each of the panelists to talk about their projects that they’ve been working on in their own words. We’re going to start out with Black Bottom Archives and allow Paige to talk about her project and the work she’s been doing.

Paige Watkins: Whatupdoe? I’m Paige, I go by P.G., and I here representing that young people who care about history and want to make sure that our voices are a part of the way that our futures are crafted. So, we started Black Bottom Archives almost five years ago, as young folks who were actually in school outside of the city. And we’re really like, where are our people at, you know, like we were in D.C., which is also was rapidly gentrifying, and we were out there and just noticing the ways that we would tell folks you’re from Detroit, like what they would say, right? And the questions they would ask us. And we knew that that wasn’t the representation of our city that should be out there, right? And we’re like, okay, where can young people go to hear about the city as it’s happening right now? Where can folks get information about the current narratives that are being shaped in the city and the work that’s being done?

And so we started a blog! And had our friends start writing op-eds and submitting creative writing, and that grew into an online magazine where folks were able to submit writing, in order to shape and change narratives about our city. And it’s been amazing actually, the ways that we’ve been able to reach nationally, right. We’ve had folks across the Detroit diaspora reach out like this is an amazing opportunity for me to keep in touch with the city and for me to know, from the perspective of folks who have been living it, what’s been going on, and that’s been really special. Currently, we’re working on two main lanes of programming. The first is our Youth Archival Fellowship program. We got to work with four high schoolers in order to teach them the technical aspects of archiving, like the different tools and technology that archivists use. They got a chance to practice what it means to be an oral historian and practice interviewing their grandparents and folks around their neighborhoods and in their churches, in order to create these projects that highlighted their histories. And it was a really beautiful process. It was an experiment, we’re excited to continue doing that with youth across the city in future years.

The other main programming that we’re doing right now is developing our digital archive of Black Bottom history. I need to name that this has been in partnership with Black Bottom Street View, which is the project that also exhibited at the Detroit Public Library‘s main branch this year, which was a panoramic street view imaging of the Black Bottom neighborhood, that was taken from the Burton Historical Collection from the Detroit Public Library and compiled into these beautiful scenes where you could literally walk through the streets of Black Bottom. And we had folks who lived in Black Bottom, right, or lived near there and played there, and worked there, went to school there, who visited and were able to say like, “wait, I know that place, like this is the route I walked to school!” And that is powerful. It’s powerful for folks to be able to do that. And it’s powerful for young folks to be able to know that that existed and that there are folks who still know that that existed.

So we want to create this resource, digital archive, we’ve been compiling oral histories, records, photos. And we want to make like an interactive map where you can click around and really go through, see the panoramas, listen to the histories. We’re currently in the part of this process where we’re getting community feedback. So we want to hear from folks who lived there, we want to hear from educators and students and organizers, folks who might use this as a resource in their work. So stay tuned to the different feedback sessions that are going to be coming up this fall and winter. We would love to have you all there and get some feedback about what we’re producing so that it can be useful and impactful for our communities.

Saundra Little: Yeah, it’s amazing. Actually, the Black Bottom Street View was one of the Knights Arts winners. So actually that was one of the first kind of panel discussions we did with them. So it was, it’s great to have you here.

Watkins: Yeah. Emily [Kutil] and I actually are using some of the funds from the Knight Arts grant to make this website come to life.

Saundra Little: Okay. That’s great. So the next project that we have is the Detroit Sound Conservancy. So Carleton, do you want to talk about what you’ve been working on?

Carleton Gholz: Hey, everybody, Paige, we should talk about how in the 90s, Lawrence Tech had a class where they did a model of the Valley before the highways. And the Sound Conservancy, when we salvaged the Greystone International Jazz Museum collections in 2015, 2016, 2017, that model was one of them. And that model is now at Dilla’s Delights, it’s on the wall there. And we are so thin-bared with so many projects, but I’d love to do some stuff around that model. There might be some value, but it’s been sitting there at Dilla’s, we put it in there when they opened up.

Saundra Little Already synergies. That’s what we wanted actually from this panel.

Gholz: It’s a meeting we should’ve had years ago. So the Sound Conservancy, we’re about seven, eight years old. We are really a bunch of nerds and archivists. The organization came out of PhD work that I had done around the rise of the DJ in the city of Detroit, and realized that there were some real holes in the history of music and dance music in the city. I did a lot of my work at a place called the E. Azalia Hackley Collection, which is part of the Detroit Public Library, easily the most important Black archive in Michigan. It’s really important, founded in 1943. And, I became a member of the Friends Foundation to try to support that archive around 2010, 2011, because there’s just been a systematic defunding of archives, of libraries, of the work that those people do and of those institutions.

So we worked really hard and actually we thought we would be a digital supplement to the physical work already happening at the Burton, the Hackley, and others, but it just so happened that as we grew, the need in the community was really intense. And so the Blue Bird is one of those places that had shut down in 2000, 2003, fell into disrepair, call it blight, call it what you will, gone through the foreclosure maze. We took one of our early photos in front of it as an organization as we were coming together, but we didn’t know anything about how to, you know, it was back when a lot of the city of Detroit had little signs on it to call for the buildings. And they went nowhere, to voicemails that didn’t exist. And, it was very scary.

And through a grant from the Kresge Foundation this last year, we were able to put together enough money to make an offer on the building, which we were able to get. And so now we own the building. And we just had an inspection in June by Building Safety and Engineering. The building was slated to be demolitioned by the city of Detroit in 2017. The City Council gets these long lists of addresses that then BSEED tells them that these buildings need to be torn down. And the City Council says, sure, they take the recommendation, as I probably would too, as a City Council person with all that information, but they don’t come with the addresses, they don’t say “5021 Tireman, the place where Miles Davis hung out whenever he was in Detroit.” They don’t say that. So it was already on the demolition list. So we had to waste a lot of time this summer, going through a process of the “deferral of demolition.” So we probably lost a summer in terms of fundraising and building around it just to figure out if we could, but we finally got an inspection. BSEED has found it to be sound and we’ve got a structural engineer coming out next week Monday to see if it really is. And so we’re just in the very beginning process of hopefully doing emergency work on the building, so it could sustain itself through the winter and give us more time to, to raise funds.

Long term, we see the venue as a potential place for an office and archive, as well as live performance space, but that all might need to get split into different pieces without funding. If there’s not enough funding there, the goal has to be just to save the building, preserve it, and give us time to raise the funds for what really is needed, which is we need to invest in archives. We need to invest in historical thinking. I’m a history teacher, so we got to teach history. I was part of the No Child Left Behind teachers where history was not a priority. It was explicitly made not a priority, and we can see the impact of that. So, I mean, that’s my long story.

Saundra Little: All right, next, we have the Black Historic Sites Committee.

Hudson Samuels: The Black Historic Sites Committee was founded in the early 1970s by then Councilman Ernest Brown with the vision and goal of preserving African American history through a variety of different activities. One of them focusing on Michigan historical markers, which were around the city, around the state, that identify people, places, and events of historical significance and contributions. And, that has continued up until today. We have a project coming up next year to replace the marker of Ralph Bunche who, people may or may not know, was the first person of color, African American or otherwise, to win the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in bringing peace attempts to Arab-Israeli issues at the time. The image that you have up on the screen, and I’m just looking at it now, there is an exhibit at the, Detroit Historical Museum on the history of the Negro leagues and the Detroit Stars.

And a lot of people think that baseball really began having African-American ballplayers with Jackie Robinson. And that’s just not the case. There were decades and decades, a hundred year anniversary of the Detroit Stars, which was a Negro league team here that played up until the time that baseball became desegregated. And what you see there is part of the exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum that really goes to the players, the teams, there were Black women, talking about Black architects, there were Black women who played baseball. There was a Black woman, Minnie [Forbes], who was a Black baseball coach-owner of a Negro league. So that’s a lost chapter in America’s pastime, And so this is what this exhibit tries to tell the story of. If anybody has been to Comerica Park for a ballgame, there is a plaque that’s dedicated to Turkey Stearnes. That’s acknowledging Turkey Stearnes as a player of the Detroit Stars, and it’s a bronze relief plaque, very nicely done. And that’s one of the contributions that’s an acknowledgement of participation, but it only scratches the surface. And the Black Historic Sites Committee has bus tours and other programs and events all around bringing to the public the history of African American contributions to the city of Detroit.

I’m going to turn it over to David now.

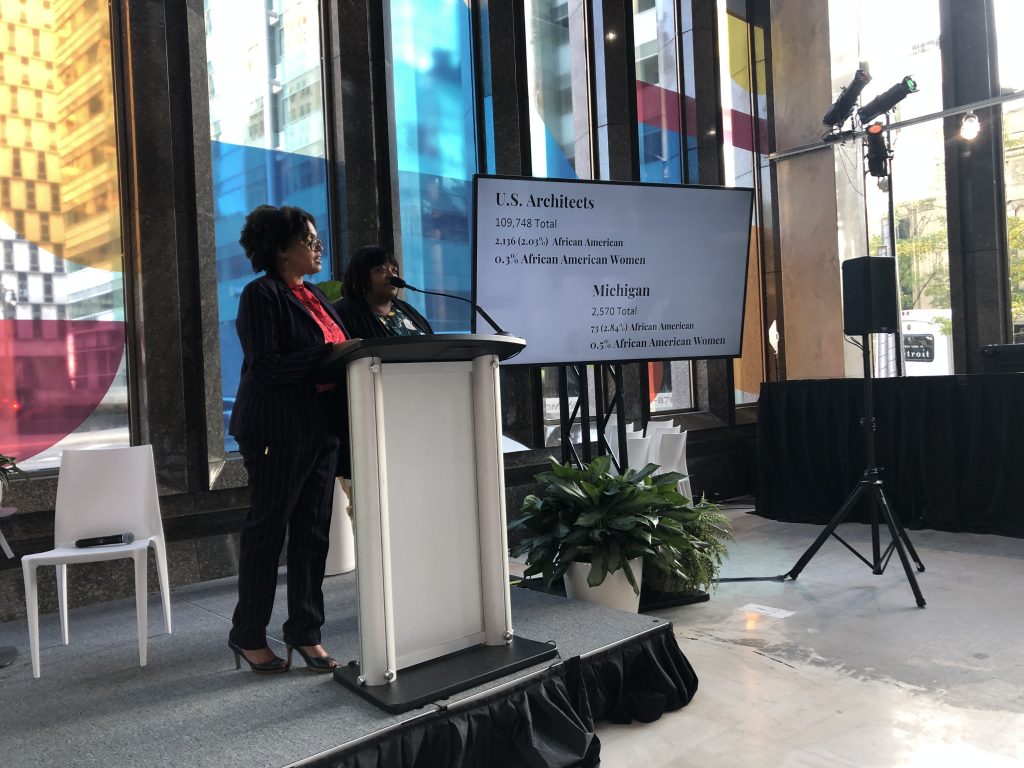

David Head Thank you Karen. There’s so much history hidden in plain sight, wherever you go, in America and beyond, about African Americans’ rich heritage. And it’s really untold. And I like to applaud the extra effort, extraordinary effort of Saundra Little and Karen Burton for bringing this panel together and sharing the rich history of Black architects in the city of Detroit and in the state of Michigan. Black lives do matter, but Black minds matter as well. And that’s why it’s so important to bring out the geniuses of Black minds that modernized the city of Detroit. And we did a beautiful bus tour about three weeks ago, and they was our tour guides. And there’s so much rich history all around us in the city of Detroit that we have no clue about. And so those stories need to be told over and over again, through different creative mediums.

But beyond that, I am the cofounder and coordinator of “Meet the Scientist Saturday” at the Charles H. Wright Museum. When I came to the city of Detroit, I’m from New York, and I had a very special project about Granville T. Woods, and I was able to get him acknowledged for being the key inventor of the New York City subway system. When the subway shuts down, New York City basically shuts down and a Black great mind, genius was able to modernize their transportation. So they embraced my research and integrated it into the “Inspiring Minds” exhibit. And I noticed that most of the their inventors or pioneers have passed on. So what I do is bring up modern day trailblazers, African American men and woman in science, technology, engineering, and math. And we’ve been doing that since 2013. And I had so many rich inspirational stories to share with these young kids who are curious about science and get them more involved with STEM paths. Beyond that I’ve created a Metro STEAM collective of engineers, architects, mechanical engineers, and historians to share this rich history in the Detroit Public Schools right now. And so I’m willing to work with all parties to share that history, especially to the youth. So I can go on, but I’m gonna pass it to my colleague here.

Nielbock: My name is Carl Nielbock and I came here to Detroit in 1984 to look for my Black father who was a GI in Germany. And I was born at a time where emancipation was not their reality, so it was illegal for my Dad to fraternize with my mother and, out came me. So he was sent back to United States and I stayed behind in Germany. I received my education in a Catholic monk school that exercised the skilled trades that a Catholic church might need. From stained glass windows to gold-bonded books to metal work. And when I was 14 years old, 15 years old, I was introduced to the scale of skilled trades that I can enter. I only saw this metal guy strike the anvil and produce sparks and was forging along. And I knew then that that’s what I want to do.

And so I entered into a former training of blacksmithing and architectural ornamental metalwork. And, that was my talent. It came very easy to me to emulate the trademaster that everybody admired, everybody catered to. And my admiration to the ability of this old man to be on top of the food chain, or to be old and frail but that the knowledge and the know how that he had in his skilled trade that make him the leader of the pack. I didn’t know it then when I was a little boy, but in retrospect, that was what fascinated me. And so I ended up like on the top of my class and, I had a studio real quick in Germany after national service. But then when I reminded myself like my Dad here in United States, I had to just go come and have to look for him.

And the only thing in my pocket, I had the certificate of the skilled trades. I didn’t have any money. And, make the long story short, I couldn’t really get the formal training as an artist in fine arts. The school system wasn’t even open for people of color then. And so I was left with SBA, Small Business Administration. I wanted to work for the White House anyway, so, there was a way to realize my drive to be in business to promote my skilled trades. And my first project that I ever really did, that was significant, it was the Fox Theatre restoration. It was the first major restoration that ever happened here in the city. And when I walked in there and I say, “I’m the guy for the metal work.” They showed me their blueprints and partially it was written in German!

And I identified all the skilled trades that I learned from those monks in Germany. And I made a bundle. I made so much money on this one project. And I was adhering to National Park Service standards and guidelines, and the highest requirements that my skilled trades in Germany, the old guys, their standards. And as I got my business going, the next project was the Michigan Bell Building, the entire exterior, whatever you see ornamental there. And later I found out it’s just like Parducci! Parducci working for Albert Kahn, took care of all ornamental aspects and stone, metal, and so on, decorated this city right here and make it to the “Paris of North America.”

Those value-creating propositions, I’m advocating not only for me, but this must be available to the young man and women that are not academically inclined, not graduated, to 75% of the Detroiters that are here because the education is not conducive to their being. They are lacking the introduction of those skilled trades that an architect needs to work in this Paris of North America, to adhere to the National Park Service standards and guidelines to the historic requirements that we have right here. And those skilled trades, they are so high on the payroll that if they are promoted, the young man and women will gravitate to that, they’d be self motivated to something that sustain themselves and their family and then they also can buy a house here in the city. So, I’m working on currently to promote those skilled trades that lie dormant in the people of color that not only here in Detroit but in the entire United States, that came from one place of the West coast of Africa, from five little countries.

They came here and was brought here, not because they were lost and hunting through the woods without an aim, they was brought here because of their tremendous skills and abilities. And I have evidence of that. I’m a metal master. I amassed the largest collection in United States of metal art from the West Coast of Africa. And within that, that metal art is equal to Egyptian art, to the Terra Cotta art from the Chinese Ming Dynasty. And so the evidence is all there and the ability to emulate that, that’s what I’m about.

We’re trying to have a Play-Doh project going to introduce young men and women through this tremendous art that is in their genes, that is they are genetically related to it. And soon as they see it, you want to give them the media, Play-Doh and clay and so on, and bring them to their own genetic ability and with that craftsmanship and the ability to create their historic evidence. This is the same metalwork, like in the Fisher Building. It’s the same metal work in the Fox, said it’s the same metal work that created the art of the people of West coast of Africa. And that’s my little story.

Saundra Little Okay. He took us from continent to continent, right? Okay. Now we have the 20th Century Civil Rights Sites project with Ruth.

Ruth Mills So as Saundra had said, she and I have been working together for two years on a project to celebrate sites related to the history of African American civil rights in the city of Detroit. This is a project that was funded through a grant from the National Park Service, which actually has a civil rights grant program, and then administered through the State Historic Preservation Office who contracted with us to do this. And as the theme has been for many of the panelists, a lot of these sites are not very well known and many of them are threatened. We first worked on developing a historic context within which to understand these sites, what they were, where they, where they are, what their historic significance is. Obviously we can’t write the whole history of civil rights in the city of Detroit. We were only just really scratching the surface. So really just focusing in on the context within which to look at and evaluate the historic significance of the sites and to document their history.

I think there are so many sites that we know the surface, we don’t necessarily know what happened here. So most people, when you think about civil rights, a lot of people think about the South and what was happening there. But Detroit has such a rich, rich history of resistance and uplift and all of the things that went into that movement. I know that in recent years there’s been a lot of talk about the practice of redlining. So this was actually enshrined in the United States government, it was a policy of segregation. But how many people know that we have a wall up near Eight Mile Road road that was built as part of that program? And it was built specifically to create segregation, to enshrine segregation, and to permit the white people on the West side of the wall to get funding and mortgages? Whereas Black folks on the East side did not have that same opportunity.

How many people know that we have the first African American owned and operated television station here in Detroit? Everybody knows who Rosa Parks is, how many people know that she lived in a house on Virginia Park for 20 years, and did some of her most significant civil rights work there?. Everybody knows who Aretha Franklin is, how many people know the story of her civil rights activities and of her father, Reverend C.L. Franklin, who was a national leader in the civil rights movement, and who was responsible for bringing Martin Luther King here in June of 1963, in a walk that presaged the March on Washington? So there’s all kinds of incredible stories that are out there that we are trying to document through this project.

In addition to the context, we did a reconnaissance level survey, so basically a windshield survey going around to look at all of these places, taking pictures of them, getting some basic information on them. From there, we did have an advisory committee, which included Karen from the Historic Sites Committee and others, working with the Historic Designation Advisory Board, to give us some input and also to narrow down that list of all of the sites in the city to 30, that we looked at a little bit more intensively and did some more historic research. From there, we narrowed it down. We only had funding to do five sites for National Register of Historic Places nominations. It started out with four, we did add one and it was very hard to do that. So it was the Birwood Wall, New Bethel Baptist Church, the Rosa Parks House, Shrine of the Black Madonna, and WGPR-TV, were the five.

Just last Friday, those were presented to the State Historic Preservation Review Board, and all of them were recommended for listing. So now they have to go to the National Park Service. But one of the things that we also did was to create a context document so that it’s not just those sites that are going to be nominated, this will make adding further sites in the future much easier under that. So that’s part of the process. There’s so many: Sojourner Truth Homes, the McGee house, Orsel and Minnie McGee house. I mean, how many people know that one of the foundation cases that resulted in the 1948 Supreme Court decision Shelley v. Kraemer, which overturned restrictive covenants, was in Detroit?

That’s really one of the things that we’re hoping, that this will give other people the opportunity to be able to do more of these sites. We are also doing a bike tour will be coming out as part of this to highlight some of the sites. We’re also doing three state historical markers: one for the Birwood wall, one for the 1963 Walk to Freedom, and one for the Sojourner Truth home.

[Start of Q+A]

Little So it was a common theme that one of the big things that kind of helps with the effort, even in Carleton’s bio, it was like, he’s bootstrapping to get things going. And you have to apply to Knight Arts grant to start a project. Funding is tough in getting all these things started, but the one thing that is so powerful with each one of these projects is the storytelling and the art of storytelling behind it. I’m thinking of actually Carleton and Carl when I think about this, Carl was talking about the use of metalworks for storytelling and Carleton has a piece that just came out about placekeeping and storytelling. So to the panelists, we know these stories are important, how do we use them to get more attention to the things that we’re doing to get more funding, for the projects that are near and dear to our hearts, we love them, but how do we keep them growing?

Head That’s one of the things I’ve been thinking about: how do you preserve history in Detroit and even beyond? I first met Saundra Little and Karen Burton by doing a lecture. So lectures are good and going around the city, sharing those lectures at key locations, that’s good. And exhibits are more visual and a lecture with an exhibit, that’s even more powerful. A lot of times this information needs to be shared with the youth, the next generation, who really doesn’t think history is important, but they need to know how it impacts their life and what role they that play in the future. So a book is good as well, illustrated book, as well as even a play, if you want to really get creative, you can do a play, but I think there’s multiple ways to expose the audience about history, but it takes some thinking and of the minds with different people that can really put it together and have a presentation.

Head And to really invoke them to really get a fuller understanding of where the roots began and where we are now. Last year, there was two books that came out: The Dawn of Detroit by Tiya Miles, that spoke about how slavery was practiced in the city of Detroit from its inception, about the street names that we walk around, and those people that played a major role in African American lives. And then Black Detroit. But before I stop, this book here, Negroes in Michigan History, this is a documented history about African Americans in the state of Michigan, not only Detroit, and African American progress from 1915 to 1965. And it should be recommended reading at every school. And unfortunately, if you show this book to the teachers, they wouldn’t even know what this book is all about. So how can they teach it to the students? Not throwing the teachers under the bus, but there’s a lot of work to be done.

Watkins So I’m answering this question about funding as someone who identifies as anticapitalist. So I’m interested in imagining a world where money doesn’t exist in the way we know it and that we’re not beholden to a dollar and all that. That’s all true. And I live in this place right now and so I know money matters. And so definitely I think I’m interested in finding funding, yes, through traditional sources around like grants and things like that. But I also feel like our overreliance on institutions and overreliance on big funders or big funding opportunities doesn’t allow us to be sustainable. And it doesn’t allow us to see our projects through for many, many years, right? When the funding runs out, or when we have to continue to apply and apply and apply for another grant, that takes away from the work that we’re actually doing.

Watkins And so for me, I’m interested in finding a balance of someone who is a grassroots organizer. How can we get a bunch of really small donations, right? That maybe are sustained or it’s like, okay, do we actually need money? Or is it other types of resources we need? What are those resources, how might folks be able to contribute them? Either an in kind way or to support using them one time in order to generate funding, to create it again or replicate it. But I think that particularly when we’re talking about preserving Black history, and we’re talking about doing that for our sakes, right, for our community’s sakes, for our children’s sakes, not just for us, not just for our clout or our notoriety or our recognition, but for the future, then we also know that we can’t be beholden to institutions and to the state and to people who quite frankly don’t care about our communities, have showed us time and time again that they aren’t interested in investing in our communities and seeing us thriving.

Watkins That’s up to us. We do that. Our people do that. Like they don’t do that for us. And so I think we have to be invested more collectively in grassroots structures around funding, how we can be resource sharing across projects that are doing similar work. How can we be funneling opportunities to each other, right? There are a lot of programs in the city who get funding over and over again, they’re the people who always get the grants, right? And that’s real. And it’s also, like, where are you in passing those opportunities onto people who haven’t gotten a grant yet? Or, where are the folks who have the money to be able to afford it supporting these programs? I don’t believe that anybody should be a billionaire when people are hungry, when there are still basic needs needing to be met, when there are still people who deserve to know this stuff and have access to this history.

Watkins I think we all have to be collectively committed to changing that paradigm. And so that means really being imaginative, being really creative, loosening our binds to these institutions and to grants, which is hard for me to say as somebody who is literally constantly writing grants. I get it, I understand. And I’m also like, I don’t want to always be doing this. I didn’t start this to always be asking for money. That’s not actually what I want to do. I think part of our job, part of our responsibility is supporting each other and supporting our projects in such a way that we can self rely and that we can self sustain. Easier said than done. It’s going to take a lot of work, small slow progress, interdependence and collectivity. But I believe that it’s possible. And I think that spaces like this are necessary because it’s like, okay, I know you now, right? Let’s have a conversation. What are the ways that we can collaborate and connect and sustain both of our projects over time?

Saundra Little That was it. That was the whole dream of putting this thing together. Well said, well said.

Gholz I just want to echo absolutely everything here. The project that started the whole Conservancy was a Kickstarter for $5,000. Small donors is really the only place where we’ve really ever gotten true satisfaction to projects, really seen it the way we want it to see it. When we’re working with grants, we’re always shoehorning it, it seems, in other people’s dreams and other people’s divisions. I just want to shout out Michelle McKinney here in the front row from the Charles Wright, who’s the main archivist here at the Charles Wright. I wouldn’t be here without archivists that had made progress from earlier times when the state did have some more investment in these struggles.

Gholz Honestly, I don’t know how many people think about Richard Austin a lot, but you know, Richard Austin was, I believe, please somebody tell me if I’m wrong. But I think the first state elected Black official, correct? Yeah, for Secretary of State, but he also ran for mayor at one point. I spent my spring break reading Michigan History magazine, because, you know, that’s what you do. And I’m reading every issue from 1969 through 1987. And Richard Austin is in all of those pictures in front of historical markers. He’s there at all those ceremonies right in the 70s and 80s, just as neoliberalism was rising and the funding was starting to be pulled out, right when our dreams were instead of getting grants, right, we were talking about tax incentives, right? That’s all neoliberal economic policy. And Richard Austin, that was just the time where African Americans were making very serious progress in some of those areas. The sesquicentennial, 1987 committees for the 150th anniversary of the state of Michigan, Richard Austin was part of that. So was Esther Gordy Edwards. The Motown Museum historical mark went up in ‘85.

Gholz So there’s all this energy there at that point, you know, the Wright was coming online and we actually got a museum. And so there was all this momentum and that momentum came from the people that I was looking up to. Leslie Williams at Fred Hart Williams and Barbara Martin and Michelle and all these people. What we have now though, is we officially have 50 years solid of retreat. I’ve lived my entire life in a state that has been retreating from every responsibility it can find. I fought for a historical marker for United Sound Systems and local historic district status because I know through the law that that’s the best way to protect United from a highway system. But at the end of the day, the system is broke. The Michigan Department of Transportation, the people who bring you highways, own United Sound Systems, the place where “Flashlight” was recorded. So we absolutely at a point, and I speak for a Board who are my bosses, so I’m speaking for myself right now, that we absolutely need a revolution, because that’s the only way a lot of stuff will change.

Hudson Samuels You know, they say journalists write the first chapter of history, that’s what you learn as you’re coming along as a journalist. And so I want to have a kind of unique perspective on fundraising. The way of the Banks Broadcast Museum started, we had our first fundraiser when we began in 2014, where we had an event that was a fundraising event. We were fortunate that we had a private business owner in the International Free and Accepted Modern Masons who stepped up and provided funding. We had a GoFundMe campaign. I think African American business owners need to be part of the contribution to preserving history. Going after grants all the time, there are a couple of rails that we need to do along with the grants. We need private funders, the Skillman Foundation. They came out along with some other folks to support the young people, the Detroit Youth Choir that everybody saw, they were in the Spirit of Detroit.

Hudson Samuels They raised a million dollars in days. Building public awareness of the importance of history and preservation is something that needs to start, I think, with journalists, as part of everyday conversation. Talk about the Birwood Wall and redlining. The Birwood wall is a concrete, 3D example of redlining. Anytime they talk about housing discrimination in the media, they need to mention here is the Birwood Wall, which historically segregated blacks and whites and the Federal Housing Authority was allowed to discriminate and not provide loans to African Americans. So building public awareness and threading it through all of the different avenues is very important. And I think it’s always a challenge, a recurring challenge. And I think new business funding models may need to be developed so that we can continue all of the work of everybody here that’s been phenomenal. Moving forward into 2020, boy, we need to have some new models. We need to get the word out so that people know and start a career in journalism. And still that’s my passion, we write the first chapter of history, but we don’t tell it every day. We need to build more public awareness.

Nielbock Funding, I greatly funded myself. And this was just out of necessity when I came here. The first funding person I looked at is my Dad. And he told me to get a job, you know, so, I tried to get a job, but, being in business was really the thing to do. And I really want to appeal on the ability to be sustainable in a city that used to be the richest city in the entire United States. It was the “Paris of North America.” And just the bare bones in our historical districts, they are identical to Grosse Point and parts of Bloomfield, which are by coincidence, two of the ten most affluent communities in entire United States. So we having, as Detroiters, a housing stock, a historic heritage that if we learn how to manage that, how to showcase it like any other city, in Berlin and Gratz and Italy and any other city have a great plan of historical economy. And that is not just showing those things. Those things need to be maintained, reproduced, made and to reflect the society that we live in right now.

Nielbock If you look in Detroit, there’s only one, a sculpture that reflect the people of color here in Detroit that’s the Monument to Freedom and they’re trying to get out of here. There is nothing in this landscape that shows a small child, little children that there was people of color had made accomplishments and contributions to this place right here. And this must be done in a realistic portrayal. In a likeness besides contemporary and modern. But that academic art is almost like classical music. To make sculptures and monuments that fix up the buildings that put in place reminders o the price has been paid from another generation. And everything that I learned from my Dad and about Detroit, the input that people had, this is not visible, in the future city,

Nielbock This is the Design Festival. And yet you walk around right here and nothing reminds you of people of colors’ accomplishments. It’s the same with the Native Americans. You walk around the whole city. Right here, there used to be the Ottawa Indians and so on. You not even would know that they used to live here. If we don’t bring our young people, that’s not working for everybody. You know, in Germany, skilled trades and producing things with your hands and working in a historical context is one third of the economy. So it can be one third of Detroit’s reality. And we have Historical Advisor Reports, we have Historical Designation Boards. And if those boards are demanding the same skilled trades that need to be implicated in what originally built this, you can’t 3D print this. There is a future for young men and women to learn art deco stucco work. Painting, not mural painting, but paintings that may be required in the Guardian Building or in the Fisher Building.

Nielbock Those skilled trades that give you a reality for yourself, a service that you can carry to the marketplace or product that you can make and carry it to the marketplace. And this is both to make our city pretty to take care of our historical districts. They could have the same economic impact like Grosse Point, because they’re done by the same architect, they have the same Pewabic Pottery tiles, and they are done by the same people. And if we are infusing the guidelines that are mandatory for historical properties, ensuring that this stuff is around for the next and the next and the next generation and teaching those skilled trades that originally built this place here in the richest city in entire United States, that was done without 3D printing, that was done by people, they worked with their hands and had skills that came from all over the world here to this one point, to be able to realize themselves. The pay for those, there, there’s gotta be a census done on how much pay and what are the wages if you engage into something. .

Nielbock We’re not even having schools are all trade masses, they could administer something like this. This requires like UNESCO City of Design, the exchange of practitioners. They just now build back the church at Notre Dame. The Notre Dame Paris burned down. The money was available, the ashes wasn’t cold. Detroit is just like the church in Notre Dame, this was the Paris of North America. If promoted proper, we can demand the resources that it’ll take to put it back into place. And the putting back in place got to be made available to the people that live here. That education that requires technical knowhow, skills, and ability that is not tapped into. Every person here is forced and pushed into an academic education, which we as business owners, as leaders of organizations and having historical titles all over the place, we are the responsible people for this next generation. If we don’t do it as these right things, those young men and women, they’re running around aimlessly, they are not feeling that they’re part of this future city, of what is about to happen. And this will cause greater social unrest versus we all getting there together.

Mills I think this idea of giving people space to tell their own stories is critically important. It’s the stories of the people that live here and that have lived here and that have something to say. I’m thinking about when we were at the review board meeting last week and Reverend Gary Bennett came from Shrine of the Black Madonna and spoke. I mean, it was just incredibly fascinating and riveting, and we just sat there, you know, telling his story of his participation in the 1967 Rebellion and growing up in the city of Detroit and being able to testify to what it was really like, I think was eye opening for a lot of people. So I think that that’s capturing those histories and I really would like to see oral histories. So many of those people we’re losing them every day. I think it’s really important.

Little Yeah. That’s what drove our project as well. So we’re going to have to go into a rapid fire answer around, but is there open it up to the audience? Are there any questions that anybody has from the audience for the panelists?

Audience Member Hi, this is in reference to Carl, about the skilled trades. One of the things that I was going to say to him, because everything he said was very factual, but one of the problems in this city is education. So when you take away the education system and you all know what the education system is in the city of Detroit. There you have totally destroyed a demographic population of young people who are not getting the education in a very dysfunctional situation. Because in earlier years in Detroit, you had organizations, private funded or grant, that would go into schools and solicit skilled trades, apprenticeship programs, all kinds of things where children who were struggling with academia on a level that was not given to them. Because of course, most of the teachers were not educated themselves in how to deal with dyslexia or autism or these types of things. And so when your whole education system in the city has crumbled and fell, that is the beginning of not being able to connect with organizations such as yours represented today.

So now what has to happen as a community, we have to engage ourselves, force ourselves, push ourselves, to connect with each other individually, if we own a business, if we are a private institution, we have to reach out to [?]. We have to go to these places and say, listen, this is what I want to offer. This is what I want to do. But I will say that the education is the number one reason this city is in the crisis it is in with not having the skilled trades. That was very important 40-50 years ago, the education system has failed the students. And that is the reason you and everyone up there don’t have apprenticeships and people who are involved in wanting to continue legacies and craftsmanships, information, archival preservation, restoration, all of these things which was here! Because I’m a product of that. I’m a product of that type of education. I’m a textile conservator. I’ve worked for Charles H. Wright. I’ve worked for the DIA. I’ve worked for Henry Ford Museum. I’ve worked for all these institutions as a private contractor, because someone along the way gave me opportunities when I was learning through the education system. So we need, that’s what we need to focus on. How do we get the students in these schools where we are already having a problem with our education system?

Hudson Samuels Two or three little words that I like to offer is that I recently went to a family reunion and I took with me many pieces of Detroit and many pieces of Georgia. Like a hundred plus year old portion of my great grandmother’s door. Soil from the ground, you know? And I took these things, the iron that I ironed with on the stove before there was electricity, to show the younger ones that this is where we came from. And it starts off so small, by having family reunions and telling each other, go in the pots, go look in the pot box and see what you can find, because you’d be surprised that there are pots and pans that are very educational and educational and advantageous for you to know about how these pots were made. Why were they made and what was cooked in these pots and where did they come from? So it can start off very, very small. And I can remember Joe Louis sitting in my class because his sister was my teacher. I remember the name Clegg not “Cleesh”. And so there’s just so many, many things that we as people have to offer, whether you went to Central, you went to Miller, or you went to Mumford. But we could offer so much to each other because of our backgrounds and where we came from and who we are. And that’s my 2 cents worth.

Michelle McKinney I’m Michelle McKinney, I’m an archivist at the Charles Wright. And I was married to this guy who was a Ghanaian. And he talked about how, when children graduated from high school, they had to give one year of national service. And this national service, they gave them a selection of things that were needed by their country. And so sometimes it was needed for the country to go to another country and learn how they did something there and bring it back. Sometimes it was learning how to have international trade. Sometimes it was learning manufacturing techniques and they would actually be taken to highly skilled people. And they would learn that trade.

McKinney So they had to have at least a year, and sometimes at the end of that year, the young adults would be more fit for going on. They will be kept by the companies they were with, or they will be kept by the organizations that they were working for. I said, wow, this is all over Africa? He said, well, “I don’t know about all over Africa, but it’s done in many countries in Africa and especially in Ghana.” So I almost feel like it could be like a league or a, I don’t know what the word is, union, that could be an extension of national service that, like they have gap years or something like that? So maybe we could even institute that and talk to our schools, our public schools and have that sort of programming going on that somebody can elect to do it. Maybe it wouldn’t have to be mandatory like it is in Ghana, but it could be something that people could elect to do.

McKinney Not everybody is suited for academic. They are suited for skilled trades or to be some sort of profession that they can be an apprentice. So I think like an apprenticeship program and that all of us who are here, who deal with repositories, and who have these wonderful Civil Rights history sites. I mean, my goodness, the storytelling, the Granville T. Woods, the WGPR, The Scene, the wonderful thing that you’re doing with the website and Black Bottom. I can’t tell you how many people come to the Charles H. Wright archives and ask about Black Bottom. It is one of our most popular, I even made a Black Bottom guide to show what we had at Charles Wright that related to Black Bottom. So I almost feel like what Detroit Sound Conservancy is offering, where they’re actually going out into the neighborhoods, into the block clubs, going to the block club meetings, meeting the people who live in those neighborhoods and saying, “well, how can we serve you? We’re part of you, where we were growing out of the community, need to save this building, to save your legacy, to save your voice. This is our voice.”

McKinney So I wish that you could all join into some kind of coalition or union where you give your website link through Charles H. Wright’s website so that it could be national in the Digital Public Library. There is a Digital Public Library that is only has white people there. How can you have a Digital Public Library? There’s a national thing and not have not one Black repository in it. You would be perfect for the Digital Public Library and you still own your own stuff, but you could upload it to this national site and people all over the world can see you. If you’re not online, you’re invisible. How come the skilled trades apprenticeship program can’t be a part of that Black Bottom, Detroit Sound Conservancy, civil rights stories. WGPR Museum, how come we can’t be all one coalition of things that young people can come through and say, I want to elect to understand my place. What is this place? This placemaking is very important. Yes, yes. My children, I don’t have one child left in Detroit because the placemaking, they didn’t have a place for them here. So I think that’s what we should concentrate on is placemaking through all of us putting our stuff together, being visible online, going to the schools, and getting these people to come together and say, we have this for you, if you want it. I don’t know how you pay for it. [laughs].

Gholz We did the first conference in 2013, 2014 at the Detroit Public Library. And Michelle started us off that morning. That first morning you were the first speaker and it was all about legacy and how everyone has a legacy. And that’s where it starts. I mean, this is absolutely that kind of consortium right now, for things that are hidden. Chicago has that Black museum consortium [Black Metropolis Research Consortium]. They’ve had those kinds of models for years. So like I said, we had that moment where there was funding there, there was a Black revolution in the city, the Wright did happen. We did make progress there, there was incredible stuff, but there’s been this again, this retreat. We are all here today seeing that this is larger than us in this room. And so all encompassing, is it something that is written that we come back from this, we transcribe the audio but is it also something that everybody wants to take a part in and write something and put together a collective piece? You said Wiki earlier, Detroit Sound Conservancy started as a Local Wiki. Because we were inspired by Allied Media Conference and a bunch of other people who are just doing it, you know, DIY. And the big Wikipedia is actually hard. It’s actually hard to make a Wikipedia page. I failed many, many times to create a United Sound System page, its embarrassing. But the local Wiki, we created a, Detroit Wiki. And so we actually had a page where we wrote every organization at that time that we thought was related to what we were doing and I couldn’t get enough people to Wiki it. So we kind of just built our own website, but it’s still there. And I think that kind of energy, just to do it, just to link people, it’s really powerful.

Nielbock Can I add something right quick, please? Look, how many young people are here? And how many young people are aspiring to history? So we gotta make this sexy in some kind of way! So I want to come up with with maybe two suggestions. And I’ve arranged myself since 2012 with UNESCO City of Design. And I’m convinced that if something works somewhere else, it’s will work for you! And in Germany, I’m from Germany so I can reference to it. Any architect know that Germany got completely bombed. Germany looked like a Aleppo at one point in World War II. But in particular historical sites. And one of the most significant historical sites was the Frauenkirche, that’s the women’s church in Dresden. And that is so important. That’s was where Johann Sebastian Bach was composing. And that church laid in rubble as a reminder against war. And when East Germany and West Germany unified, they got the best architects together, the best artisans, excavated the site and built that church back up. Today, it gets 2 million people annually visiting it. It is one of the top 10 of UNESCO World Heritage. And the people has transformed their city of Dresden. They became the expert in recreating, the expert in rebuilding things that seemed to be lost. And now in Berlin, they’re building their whole Museum Island back and really significant things.

Nielbock And just like this was the place, the Paris of North America, to reinstate the evidence that made this place great. To turn young men and women on to the skilled trades that make those great things. That gives you the ability to make some money here. That that is based on your on your ability and that’s got to be rewarded too, you know, and to get there, to get there, we got to only invite those practitioners to come here to Detroit, show them the great American way. In return we fix that broken link, the old guy teaching it to the young guy and so on. But also it would reverse the myths that we in Detroit tear up everything, we’re good for nothing. We can be reversing this whole thing and become the expert in reinstating those lost artifacts. And then we have something to offer to other cities.

Watkins So, yeah, I’m thinking about a couple of things. So, okay, I completely agree with the idea that we have to make this work exciting for people, right? We have to make this work exciting for young folks. Toni Cade Bambara says about the revolution that we have to make it irresistible. And so we do that, a lot in the Black Lives Matter movement. Our organizers, we’ve been changing culture. We’ve been changing narratives because we make it exciting and we pull people in in that way. And so I think that that’s the work of historians, archivists people who care deeply about preservation, is that we have to make it feel good, right? We have yet to make it sexy. I really was with that.

Little You have to complete with the bling and everything.

Watkins No, you haven’t got the swag. You gotta have it, make it creative and fun, right? And part of that I think is changing the perception of what young people know or don’t know or interested or not interested in, right? There’s a lot of ways that older folks make generalizations. And I can say this as somebody who has spent my whole life under the generalizations of like young people just don’t do this. And I don’t know about y’all generation, y’all, you know, whatever. And these are conversations I love to have with people. “Kids these days. We don’t know nothing. We’re not interested in that. We’re messing up this and that, right?” Like, this is, this is what we’re told. This is what we’ve been told, right? This is what we go to school and get told by our teachers, by our principals, by folks who are supposed to be investing in our futures and in our development.

Watkins And so I think part of the work is changing that narrative and changing the idea, like asking “what actually are you interested in?” Not that you’re not interested in anything, but what is it? How can that relate to the importance of this historical moment? Or what about, as much as it’s important to learn about and document and preserve things that happened 20, 30, 50, 70, a hundred years ago, it’s just as important to understand and preserve the current moment that we’re in right now! We’re in a very important cultural, political, social moment. And what are we doing with young folks to do the work of preserving that? Before it gets 30, 50 years down the line? And we’re like, “Oh no, what did we miss?” It’s like how do we do it actively right now.

Little How do you have a Harlem Renaissance in Detroit? It didn’t happen after the fact, they didn’t archive that after the fact, they were doing poetry and everything right in the middle of that.

Watkins Right. And actually the idea of Black Bottom Archives was to do that. Right? It’s like this living archive, this thing of like, yes, we’re an archive, but a lot of what we’ve been doing up until we started this digital archive specifically for Black Bottom, a lot of it actually was about archiving the present moment. It’s like, yes, submit your stuff. Like, let us see your pictures. Let us see how you understand your community. Talk to us about your family and your church, right. And about your understanding of the politics here and the economy here, all of that is important too. And so I think part of the work that we have to invest in is changing the stories we tell ourselves and changing the stories that we tell young people. This summer, we worked with four young high schoolers, to teach them about archival technology and tools. They worked and they produced their own oral history projects by the end of this nine week program.

Watkins And I mean, it was imperfect, you know what I mean? It was our first time doing it. We didn’t exactly maybe do it the right way. There was a lot of things we learned about how we could better support the students in future years and how we can scale that project from the four youth that we worked for this, worked with this summer to like 10, 20, 50 youth, right, over time. And part of that scaling is about how do we keep it interesting for what they are interested in, right? It’s not like we’re going to say, you have to do this project. This is the project that all y’all have to do. But instead it’s like, here are some tools, here are some resources, here are the ways that those tools and resources have been used before by other people. What can you do right now? What are you interested in right now?

[audience member asks how she paid for it]

Watkins How did I pay for this summer program? So I’m a fiscal sponsor of Allied Media Projects right now. And, through Allied Media Projects and six other projects that they work with, we got a grant from the NoVo foundation, multi-year grant. And then also I’ve been, I just write. I write a bunch of grants, I just write a bunch of grants and I have a handful of sustaining donors who really hold us down. And so we’re able to do that. We were able to stipend the youth, and we were able to pay ‘em! Development and learning is work too. Right. Like we deserve to be compensated for that time and the value that we add.

Watkins So yeah, just advocating for the youth that, you know, yes, our education system has disappointed us deeply. I’m a product of DPS as well. I feel very sad for the futures of our students in the school system as it is right now. And I know that it’s not their fault and that there is brilliance. They’re cultivated and cared for and cannot be dismissed because of the conditions that they’re in are dismissed because of the perception of them or their communities based on these generalizations and these assumptions. So, yeah, very interested in figuring out how to make it sexy for young people, how to bring more young folks out to events like this and how to get folks interested in preserving not only historical importance in Black Detroit, but preserving this current moment as we see the city changing actively before our eyes, right? Like how do we make this also important?

Little Give a hand to our panelists.

[applause]