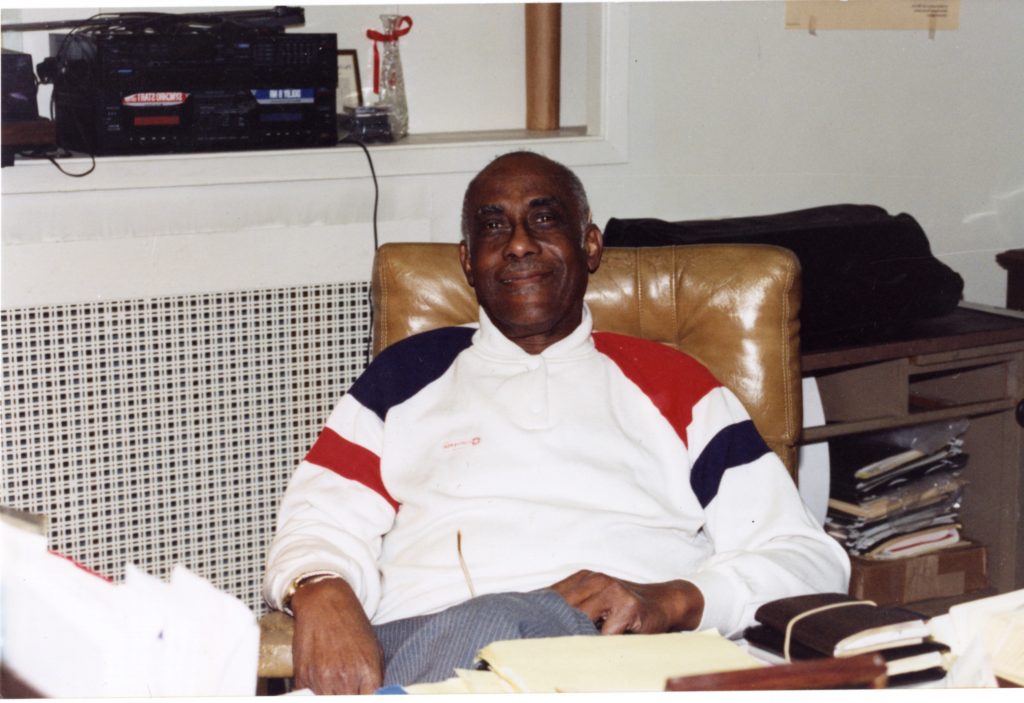

James Jenkins (1916-1994), Founder of the Graystone International Jazz Museum, discusses his motivations for starting the museum in this interview.

This manuscript is the product of a tape recorded interview with James T. Jenkins conducted by Deborah Evans for the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library on June 7, 1988. Deborah Evans transferred the tape and James T. Jenkins [1916-1994] edited the transcript.

James T. Jenkins is the Founder and Director of the Graystone International Jazz Museum. “Founded in 1974, the museum serves as a repository of jazz memorabilia which documents the history of improvisational music and the musicians who are its creators. The museum promotes and conducts research which traces the development of improvisation from its beginning in traditional African rhythms to its innovative maturation in American African forms and styles.” (Excerpted from “Detroit Jazz: An Overview,” a publication of the Graystone International Jazz Museum, Inc.).

Deborah Evans is the Field Archivist- Specialist in Local History of Afro-American and Non-European Ethnic Groups for the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer and narrator sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Burton Historical Collection is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein: these are for the reader to judge.

——-

This is the oral history interview conducted by Deborah Evans with Mr. James T. Jenkins, founder of the Graystone International Jazz Museum. The date is June 7, 1988, and we are in Mr. Jenkins’ office at the museum.

Q: Mr. Jenkins, can you make some comments on how the museum came about as an idea in your mind and what motivated you to really get it going?

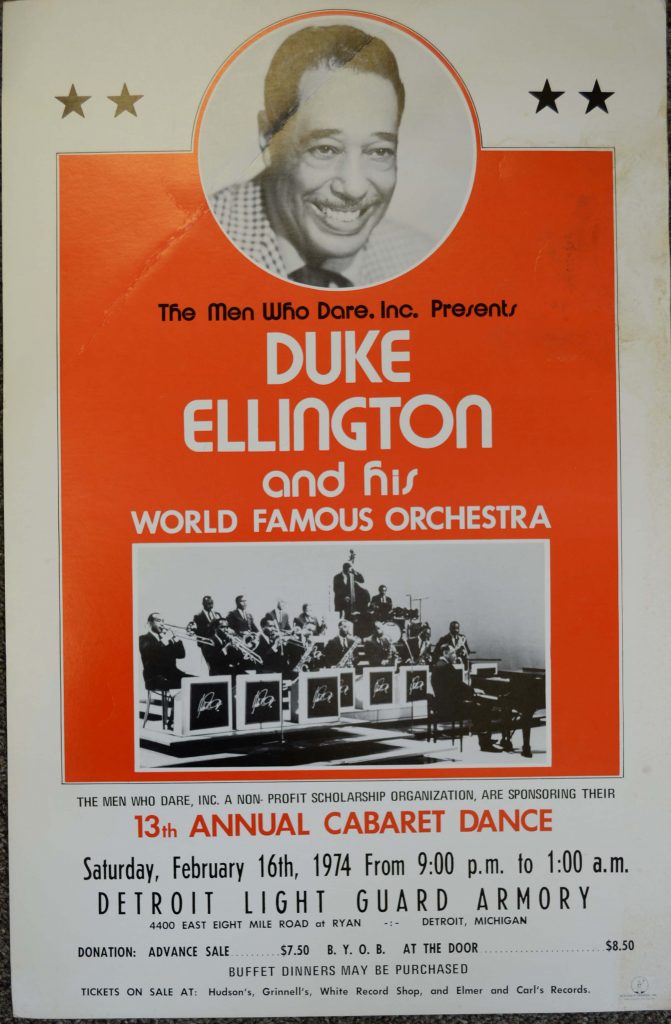

A: The museum came about through the love of music, good music that I grew up with. I’m not a musician, but I love music. I love the music that got us where we are today. And the creators of that music who haven’t received their due respect, the proper honor for these great people who contributed so much for us to enjoy, that had begun to die out. What really struck me and made me conscious of the idea was the death of Louie Armstrong. He was such a missionary… an ambassador, sent throughout the world to spread the message. Not only for music, but for culture, for relationships in government; and then a few years later, there was the greatest of all, Duke Ellington. I had the pleasure of booking Duke Ellington three months before he died. It was at the Detroit Light Guard Armory for a scholarship annual fundraiser, February 19, 1974. We honored Duke that February with a plaque and with keys to the City of Detroit from Mayor Coleman A. Young. Duke was too sick to come to the celebration, so his son, Mercer Ellington, planned to take the honors. Fortunately, the evening of the performance at the Light Guard Armory, Duke appeared. I persuaded the Ford Motor Car Company to donate a Lincoln Town car to transport Duke around that Saturday, and Saturday evening, to the function. The city declared that day, February 19, 1974 Duke Ellington Day. Duke was staying at the Statler Hotel on Washington Boulevard. I drove Duke from the Statler Hotel to the armory for the affair. Duke and I conversed all the way to the armory, and he spoke great things about the music, as sick as he was. (At that time he only had a few months to live). He had great aspirations and visions of where he wanted to continue to go, and things to be done.

Q: He still has a vibrant mind…

A: Yes, he did, he really did. So, when we arrived at the dance, he was given a private office with a couch so he could lay down and rest. Then, he would perform ten or fifteen minutes out of an hour, and be relieved by a pianist traveling with the band. But he loved the public so…he didn’t want to disappoint them completely.

Q: So that’s why he did at least fifteen minutes out of the hour…

A: Ten or fifteen minutes, and then he would have to get off the bandstand and go back into the office and lie down. He performed until there was only about thirty minutes left in the affair, and he asked to be transported back to the hotel. While I was driving him back, he told the friend with him, “Get Mr. Jenkins’ address—I want to send him a Christmas card.” And I said, “Mr. Ellington, Christmas just passed. You’re going to send it next Christmas?” And he said, “No. I don’t send my Christmas cards out until May of each year. My Christmas cards never get hung up in the Christmas mail.” So they took my address. I delivered him to the Statler hotel, and watched him enter the hotel. We had some special posters made, publicizing his performance in Detroit, and he wanted me to bring him some the next day before they departed for their next gig. I delivered a dozen or two of the posters to him at the hotel. Not realizing Mr. Ellington was near death, I went ahead with my usual routine, and one morning in my travels, I turned the radio on, and they announced Duke Ellington had died early that day…May 24, 1974. It was a tragedy, such a shock.

Then I began to think… where is the memorabilia, the honor and respect for these great legends who were dying out. We didn’t have a hall of fame, we didn’t have anything to honor them. I felt there should be something built so these great people could be given respect, and be remembered and honored. Since I was very knowledgeable in the promotion field here in Detroit, I talked to other musicians and people in the promotion business, and we decided to get together and build an international jazz museum and jazz hall of fame.

Q. How did you pull these people together, and how did you pull the resources together to move it from an idea to a real entity.

A. Well, somehow, I was respected here in promotion. I had reactivated something that had died in the late forties and early fifties, and nobody was bringing in the big bands to play for dancing. There was a segment of the population that nobody did anything for… they just cast them aside. If you were over thirty-five, they felt you should go somewhere and sit down and…

Q. Be quiet?

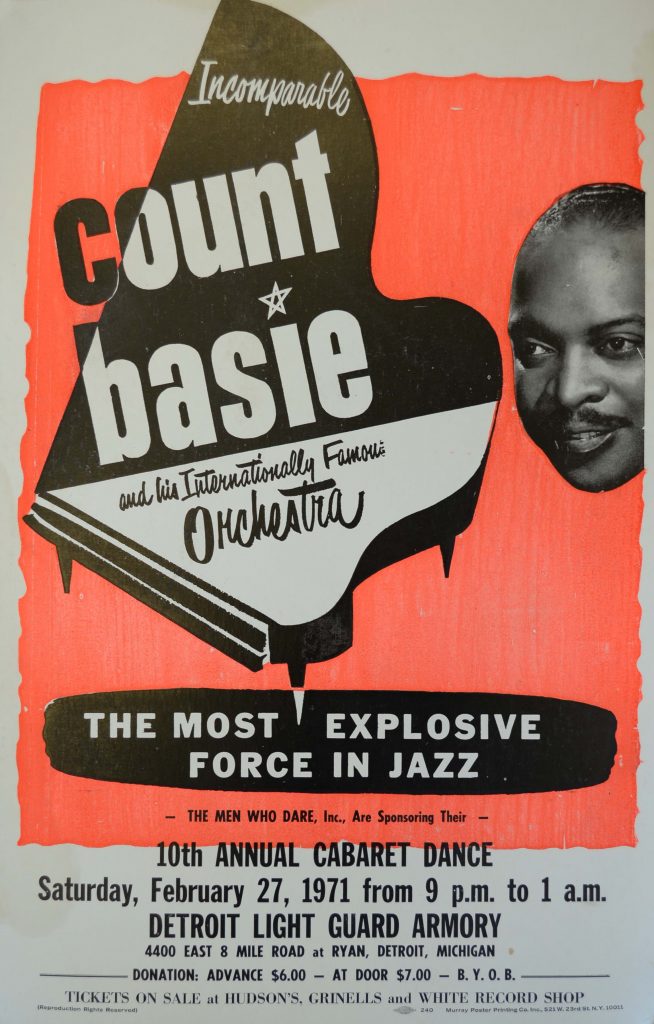

A. That’s right. There was plenty of support out here for big bands, but somebody would have to take the gamble to bring them in and promote them. So, the first affair we had was the Count Basie Band. And quite naturally, to say that you’re going to pay a band $4,000 for one night, and your budget is very lean, you’re taking a gamble. Then you’re having an affair in mid-winter, in February, and a snowstorm or ice storm, or something like that…. could wipe you out. Then we advertised it, and oversold it. We were supposed to sell about 2800 tickets, and we miscalculated some way and sold an extra three or four hundred tickets. The night of the affair at the Light Guard Armory, people were standing around the wall, in the aisles, and people were outside waving twenty dollar bills…and the affair didn’t cost but six dollars.

Q: They were saying, “Let me in?!”

A: “Let me in? Will this get me in?!” (Laughter). Everybody wanted to see the great Basie. The dance was over at 1:00 and the patrons had to be out of the Light Guard Armory by 1:30. Along about 12:30 or 12:45, everybody was still dancing in the aisles, on the steps, and in the hallways. The musicians just loved it. Basie played and played, and oh, my God, they just partied! So, that was a sign that we were doing something right, it was very rewarding.

Q: You saw a need there that people wanted this…

A: That’s right. Then, then next year we brought in another big band. People were calling, saying, “Who are you going to have next year?” “Can we do this twice a year?” They were all saying, “This organization does something for us…let’s support it.”

Q: So you feel that museums need to have the commitment to the community, to meet the needs of the community—that a museum doesn’t just exist separately from the community.

A: I feel that the museum is a representation of the past. It’s education and culture. There is a future in museums, too. These people who have played, who have gone on before, the legends…they have set the tone and left us a map to follow. Then we can bring in young people, people who are aspiring and want to become a protégée of these legends. They’ll have some background to work on. Museums do not have to be totally non-profit. There can be a subsidiary part in this promotion, if we have a performance hall, and have places where people can come to perform for a stipend.

Q: Or a banquet hall!

A: That’s right. And then we’ll have workshops, we’ll have the great musicians come in and lecture and demonstrate to these young people. We’ll have teachers come in and instruct these young people. If we don’t do it, the corporate people aren’t going to do it because they are for profit. If it doesn’t sell, they don’t want anything to do with it.

Q: So the museum as an entity was started in 1974?

A: At the death of Duke Ellington. That’s when it started.

Q: What was the first year like?

A: Oh, it was glorious. We had great aspirations. You got good vibes from everybody. I’ve got letters in my file from Coleman Young. I’ve got a letter from Henry Ford, II, –and letters from all of the big entrepreneurs because I wasn’t afraid to ask.

Q: Do you think that’s the key?”

A: Well, we never did get control of the building. A representative of Motown said if we became a viable organization, and came up with the right kind of tax-exempt status with the Internal Revenue, they would consider donating the building. In the book Requiem for a Ballroom, it shows the big wrecking ball up there beside the building, and they hit the building August 19, 1980. I was down south, taking care of some business, and there was no one here to lead the group who had any authority, or knew the direction. When I got back, one side of the building was torn down, and they were trying to get an injunction to put the building on the Historical Register and stop it from being torn down. That didn’t happen, so, we lost the building. All of my supporters left, and everybody said, “What are you staying in business for?” So I said, “Well, we can build a jazz museum.” The jazz museum was supposed to have been a part of the Graystone building: a training room, a meeting room, a museum, a jazz joint and an outdoor garden.

Q: So you were thinking of an entire complex.

A: That’s what it was. The lot that was south of the Graystone, where they had torn down a building near Garfield, was envisioned by me as a four story parking ramp that would lead into the Graystone. You see, in that era, everybody was exiting Detroit. Everybody was leaving, everybody was laughing at me. “Who’s coming down here to the affair?” Dwight Haven was the president of the Detroit Chamber of Commerce and he did everything he possibly could to get some big executives or corporates because he believed what we were saying.

I was just a little old bus driver, here for thirty-two years, you know, I was not supposed to have any sense; I was not supposed to have any vision; or any talent for leadership.

Q: So, if someone has that point of view, they’re not going to come to you and say, “What do you think?”

A: (Laughter.) Some of these people told me years ago, in other words since 1980, that I didn’t know what I was doing, but I must have done something right to hold this together. I found out that you’ve got to get an accountant to account for all of your money, and take care of your bills, and know how to figure out the financial reports. People a lot of times don’t mishandle money, but they try to be an impresario, and do everything, and some things fall through the cracks.

Q: They make an honest mistake?

A: They do. The foundation is laid. Behind every report that I send to the Detroit Council, the Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, the CEC, and the Michigan Council, I send a CPA report.

Q: At the local history conference, you talked about the outreach programs. I wanted to talk a little more about that. You mentioned workshops, and also outreach to nursing homes…

A: Oh, yeah. These are professional musicians who go out and entertain people for an hour and a half. It doesn’t cost anything for them. We go to Boys and Girls Club on Collingwood and Petoskey; we go to the Youth Home on Forest; we go into schools; we also go into nursing homes like the Walker Williams Center…

Q: How are you received at the schools?

A: The greatest experience I had was Southeastern High School, this past November. We carried six musicians and they did one hour and a half lecture and a work demonstration, playing and lecturing to those students. There were thirty-five of them. You would almost cry to see the attention given to those musicians; the questions they asked; and the different music that they knew. It was a music class over at Southeastern, and we intend to go back this fall and do a lecture workshop. We also did one at Country Day School in Birmingham.

Q: So you’re reaching out to a lot of different communities.

A: That’s right.

Q: You have a Friends Group at the museum, is that correct?

A: Well, we have a Friends Group that’s just beginning to gel, and do things. It’s a promotional team. You see, you’re not going to get the support of all your membership I don’t care if you have five hundred members, you aren’t going to get but twenty or thirty people to come in and work together. And these are the people that make plans, just like when we had our “Cavalcade of Jazz.” They are members of the museum, but we call them Friends of the Museum, and we hope for continued growth, because, frankly speaking, since 1985, we have made steady progress.

Q: You mentioned that you go to flea markets and resale shops to gather some of the artifacts. Then you mentioned gifts of photographs, sheet music…

A: Yes. You see, all of these photographs, they say “Richard” on them…they’re from Dick Lawson, Hugh Lawson’s father. Hugh Lawson’s father is a musician, he plays around here now. He goes down to this place with his brother, and they get down there and go to jammin’. I’ve got a picture of his father, and all of them when they were living on Mackay. Richard used to work at the Fox Theatre, when it was first built in 1928. He was working in the promotional department. The Fox Theatre used to house some of the greatest stage shows that ever played in Detroit. First time I’d ever seen Bill Robinson, the tap dancer, was on stage at the Fox Theatre.

Q: Now from my generation, it was more of movies, or whatever.

A: Well, I saw him in person. Richard Lawson used to work in the promotion department, and when a promotional package came in, three or four weeks before this artist’s arrival, he would sneak a picture out of the promotional package. And when the artist came, he’d get them to sign it.

Q: So he had quite a collection over the years.

A: He had all those collections in his basement. He was a bus driver, too, but the funny thing is, we never met.

Q: That’s incredible.

A: Until I retired. And I started this venture. Then he kept telling me, every once in awhile, “I’ve got some photos you might be interested in.” Finally, one day I went to his house, went down in the basement, and said, “Oh my God! This is gold!” He said, “What do you mean?” So, he thought enough to loan them to me, and I had my curator make copies and return the photos to him. And then Jimmy Wilkins, the big band leader gave me some photos. Some other musicians and people in the general public also gave me photos, and all I did was have copies made of them. Then Ed Mckenzie (“Jack the Bellboy”) sent me a group of photos that we’re going to redevelop now. And that’s how you do these things. Sometimes you go to a flea market and you find a lot of photos. I never let anybody know what I’m looking for. I just walk and look and ask. I’ve got some record players I didn’t pay but thirty dollars for.

Q: That’s unbelievable, almost. They didn’t know what they were giving. That’s what happened there.

A: (Laughter).

Q: So this is the only jazz museum in the state of Michigan.

A: The New York Jazz Museum went under in 1978. The English government had appropriated five hundred thousand pounds to build a multi-purpose entertainment center in Leeds, England, and a museum. So, when the press came to the Westin Hotel and saw the Graystone Jazz Museum videos, pictures, etc. that Jim Ruffner and his wife [Trenna Ruffner] were displaying in our booth, Jim said, “Well, my God, what happened to your museum I was in Leeds in 1985, and they had appropriated all that money…” They said, “It never got off the ground.” So maybe if we had a five million dollar donation, we wouldn’t have gotten off the ground either. We built our museum by flour glue [homemade paste], safety pins, straight pins, the DOT and DSR pension…

Q: Just from the basics…

A: That’s how we got things, how we collected and got things from the flea market, and how we went out and taped people. That’s how we built this. And everyone said, “How did you do it?” That’s how we did it… People say, “You have something here that’s a real attraction; something that is one of the major wonders to see when you come to Detroit.” I’ve been in Detroit fifty-three years, and Detroit’s been good to me. I took advantage of what was allocated to me when I got here. In other words, I couldn’t go into a white man’s job. I had to take the steps. Then when I was a bus driver, I built up seniority, and I knew that I could retire. After so many years, we joined Social Security, got dual support, and could make a good living. I’m very satisfied.

Q: Because you took advantage of the opportunities that were there.

A: That’s right, yes. Then, I think I have made a great contribution to the city.

I served the public for thirty-two years, I drove streetcars, I drove busses, and I was an ambassador to the public. I retired in 1973, and fifteen years later here I am, doing something special with my retirement time. I’m a citizen and still useful, I didn’t just go somewhere and sit down and watch soap operas. You understand? Or stand on the corner…

Q: You’re still contributing now.

A: I’m still contributing something to the city. Through culture, through history, and providing something that can grow, something that Detroiters can see and be proud of.

End