Jim Stone, musician, DJ, promoter, and activist, has died at the age of 54. Detroit Sound Conservancy pays tribute to this advocate for Detroit music.

Jim Stone, a music-industry veteran, community activist, and proud gay man who advocated for Detroit’s musical soundscape across multiple genres for close to forty years, died on March 4th, 2020. He was 54. According to his family-penned obituary, Stone died due to complications from a severe stroke. Though Stone was not diagnosed with COVID-19, his funeral and at least one memorial celebration have been affected by the global pandemic that has severely impacted Metro-Detroit where Stone lived and worked.

Stone was a close friend and sometime musical collaborator with our co-founder and Board President LaVell Williams who died fall 2018 due to long term complications from kidney disease. He was also a mentor and friend to our Director Carleton Gholz.

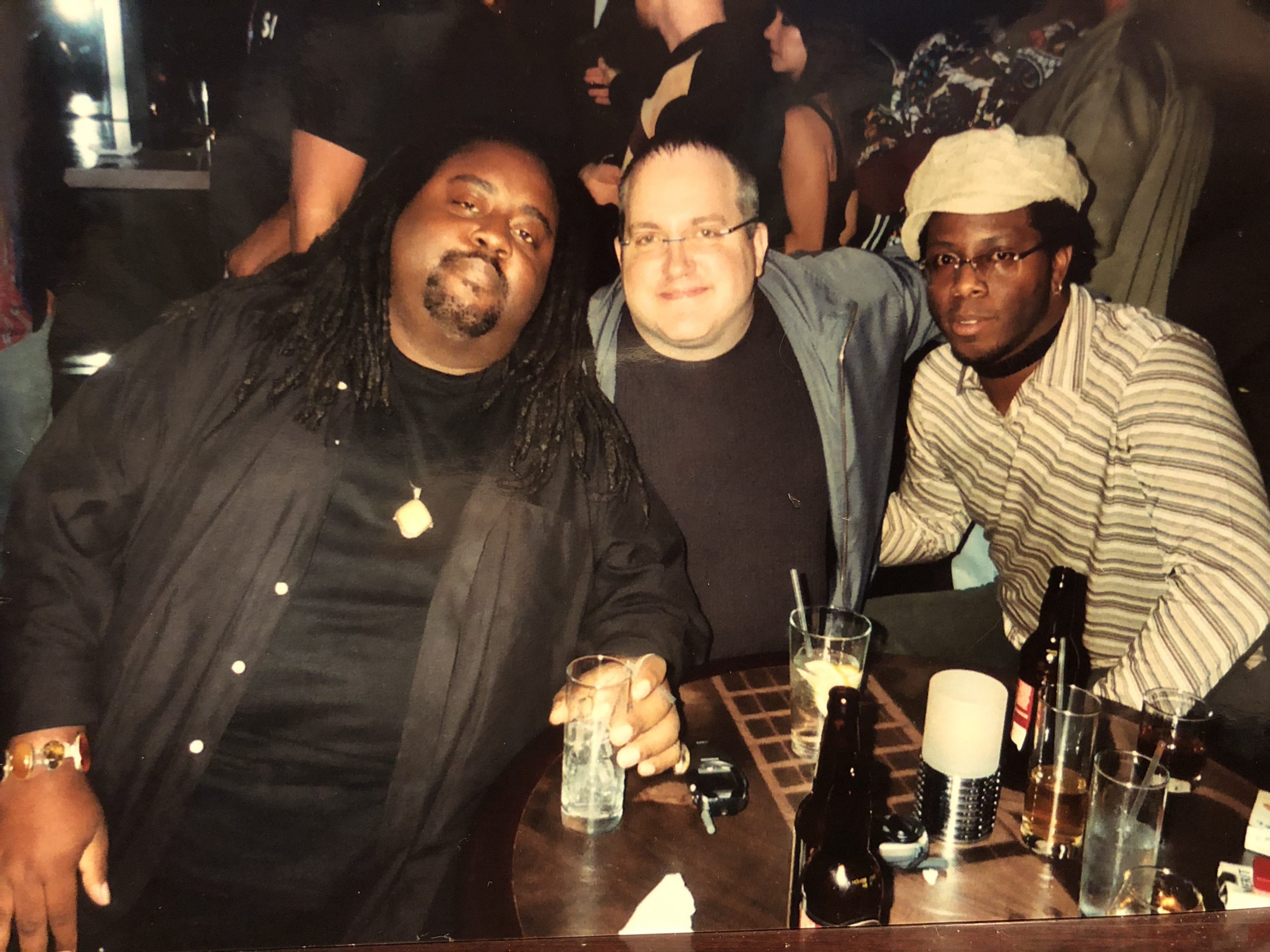

[Featured image above: Singer-songwriter and DSC Board President LaVell Williams with Jim Stone and musician John Briggs, 2003, by Kito Jumanne-Marshall.]

In lieu of Detroit Sound Conservancy participating in a larger memorial service for Jim during this time, we are taking a moment to share some moments and memories from Stone’s musical life from some community members that knew him.

The Post Rebellion Generation

Jim Stone was unique but not alone. He was part of a cohort of metro-Detroiters born during the 1960s who came of age in Detroit’s post-Rebellion cultural landscape. Despite repressive legal structures, ongoing systemic racial and economic realities, defacto segregation, homophobia, the AIDs crisis, and an at-times reactionary political landscape, these young people — approaching 60 years of age — created a multi-racial cultural movement that at times conjured a new style of living more accepting, daring, and joyful than any that had come before. Their impact is deserving of extensive historical documentation and celebration. The long term effects of this culture can still be heard and experienced during Detroit’s music festivals, like Movement, and in clubs like Motor City Wine, Marble Bar, and Menjo’s, where a hip multi-racial stew of audiences and performers continue to prepare world-class feasts.

Like Williams and DJ / producer Mike Huckaby, who died recently from COVID-19 (read this remembrance of Huckaby by longtime ally and Detroit techno griot Mike Rubin here), Stone was creative unto himself and held center stage at moments during his career. Of the three, Huckaby’s star has shown brightest of all, his premature death coming to the attention of the New York Times in April. But Williams, Huckaby, and Stone spent most of their careers putting others first. They showed up for others. They foregrounded the sounds and creativity of others. They educated others and allowed others to take that stage. In that way, they are part of a crucial tradition of musical people without which no musical scene could ever exist let alone thrive.

A Saturday Kid

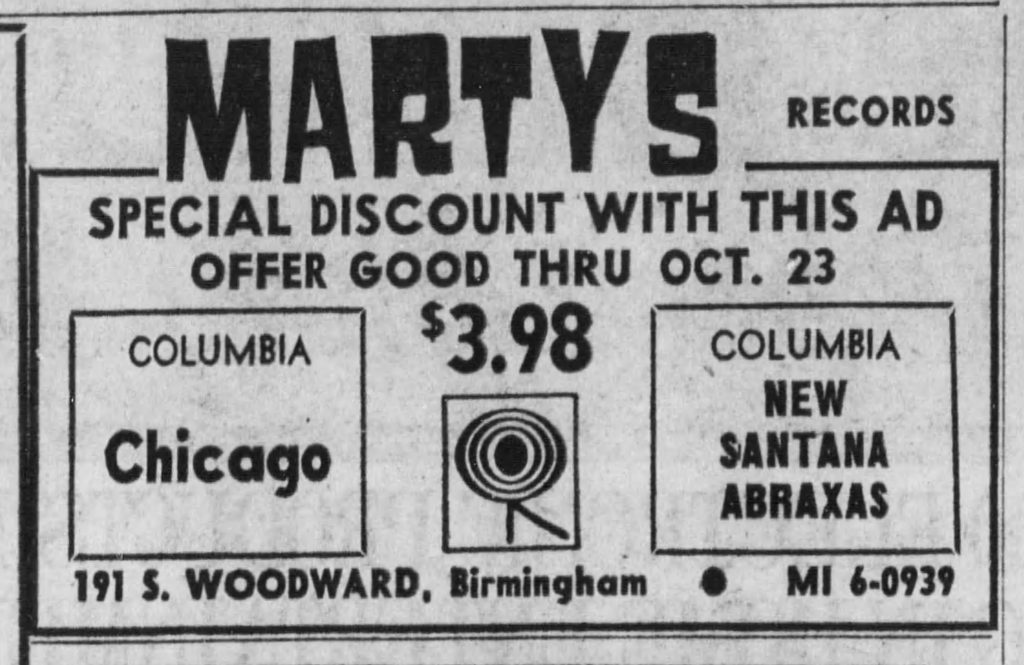

Bob McCreedy, member of Detroit alt-country band The Volebeats now living in New Hampshire but who grew up in Detroit’s northern suburbs, was shaken when we alerted him to Jim’s death. McCreedy’s Father Don, a former jukebox operator, was then the owner of Marty’s Records in Birmingham, a quiet bedroom community that for a time had a serious block of media cool that included a Little Professor book store, the Birmingham Theatre, and Creem magazine. That was where McCreedy first remembers meeting Jim Stone on Saturdays at the shop.

“Jim was a huge Bay City Rollers fan back when he was eight or nine years old. He dressed exactly like them — the plaid jumpsuit with the flood bell bottoms.” McCreedy’s look at the time was not that different, featuring rainbow suspenders and a blue jean Superfly-style hat. “We impressed each other right from the start.”

[What the Bay City Rollers perform “Shang-A-Lang” via Youtube.]

“He would spend hours flipping through 45s and asking me to play records. Each record I played for him, he would ask some very obscure trivia questions about the band or artist. He would then tell me the answer to the question. He knew everything about everything.” Stone would continue to be “one of those Saturday kids” at the store from elementary through into high school, eventually trading out boy-band pop for punk, spectator-fan to performer-participant. He was not alone. Jim joined a rabble of kids from high schools like his own Seaholm and nearby Troy who were also eager to escape their own suburban cul-de-sacs for emergent hangouts like Endless Summer Skateboard Park on Little Mack in Roseville.

Photo courtesy of Heidmous.

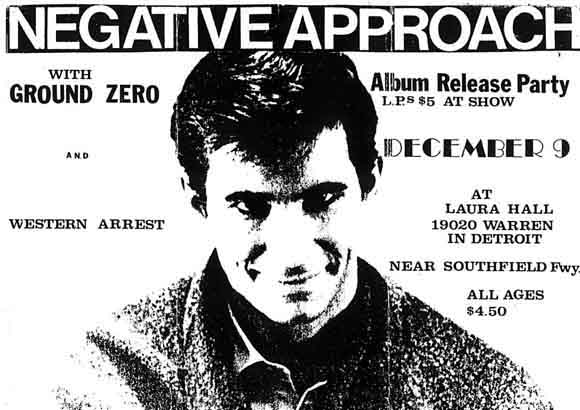

That’s the period where he met Jon Howard. Howard, longtime employee at Flat Black and Circular in East Lansing, was then just another member of the nascent Detroit hardcore scene which included bands like Negative Approach. In an online message, Howard called Stone a, “force of nature in the 1980s. Always up front at gigs singing his heart out.” Stone ended up fronting a band called Western Arrest that would open for Negative Approach at Laura Hall (formerly the Hoover Theater) on Detroit’s far West Side and record a four-song demo tape.

The Search for Heaven

But by the time Stone graduated high school and Western Arrest broke up, genre and identity were becoming mixed in ways that the Bay City Rollers could never have imagined. In 1984, the year Stone graduated, Prince‘s Purple Rain, was number #1, The Electrifying Mojo was the king of Detroit radio, and a house-techno scene which had begun on the largely queer underground margins of Detroit, was slowly but surely remixing Detroit’s nightlife culture. An older generation had reimagined Bookie’s Club 870 on McNichols, a former supper club, into a gay bar which then evolved into a punk / new wave / post-disco lodestone. For Jim’s slightly younger, post-Rebellion generation, Todd’s on the East Side became the place to crossover genre and identity. A gay-identified “sway lounge” in the 1970s, in the 1980s the converted bowling alley was arguably the most important dance floor in the city. On Wednesday and Saturday’s DJs like Greg Collier held court for a primarily Black clientele. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, a largely White crowd listened to new wave, goth, and industrial spun by DJs like Charles English. The result was a place where a new-waver with open-ears like Jim, who also was discovering his own identity, could explore multiple styles, sounds, and scenes.

All of which led Jim to Club Heaven to hear Greg’s Brother, Ken Collier, in the late 1980s. “It had a raw and gritty vibe with amazing music,” Jim told the Metro Times in 2000. “It was edgie but not dangerous.” Later, he would get to know Collier professionally while servicing him records from KMS. He remembered Ken playing Dajae with Cajmere tracks. “Ken played the shit out of that stuff.”

[Read about Detroit Sound Conservancy’s efforts to preserve the legacy of Club Heaven here.]

But during this earlier moment, Stone also experienced the Music Institute downtown. He heard Derrick May play reel-to-reel there. “I felt like I was high and I really wasn’t.”

But it was an opportunity to work with Kevin Saunderson’s KMS label from 1993-1995 that brought Stone directly into contact with the burgeoning independent music industry. He had met Saunderson at Club Taboo. Saunderson called us and left a message about how sweet and professional Jim was at his time at KMS, an impression backed up by his next boss Dan Bell. “I don’t remember exactly when I first met Jim,” Bell wrote to us on email. “I definitely recall seeing him at parties in Detroit around 1990/91. I got to know him a little better when he started working for Kevin Saunderson’s KMS label. At the time, I was a buyer for the short lived Record Time Distribution and he would call me with all the new releases from KMS and its sub labels.”

Bell continued: “After 7th City Distribution started up in 1994, Jim was our first hire. Along with myself and co-owner Kristie Negro, Jim played an integral part in 7th City becoming an important distributor for the house and techno music the world over. He was specifically in charge of domestic sales. One thing I’ll always remember about Jim was his photographic memory with phone numbers. It was common that he could recall random phone numbers from a month or longer in the past. It was actually faster to just ask Jim for a number than to consult the Rolodex.”

During his time at 7th City, Jim also began to help promote and organize gigs around what was being branded as “Acid Jazz.”

“He was the quintessential behind the scenes music person with his fingers in many pots – distribution, promotion, party promoter etc.,” says Bell.

Meredith Ledger Seller met Stone then too while she was working at Carl Craig‘s Planet E, and the late Laura Gavoor worked at Derrick May‘s Transmat. “The three of us would often grab lunch and shoot the shit. What I remember most about him was his impeccable knowledge of all kinds of music and just being the nicest guy.”

The Family You Choose

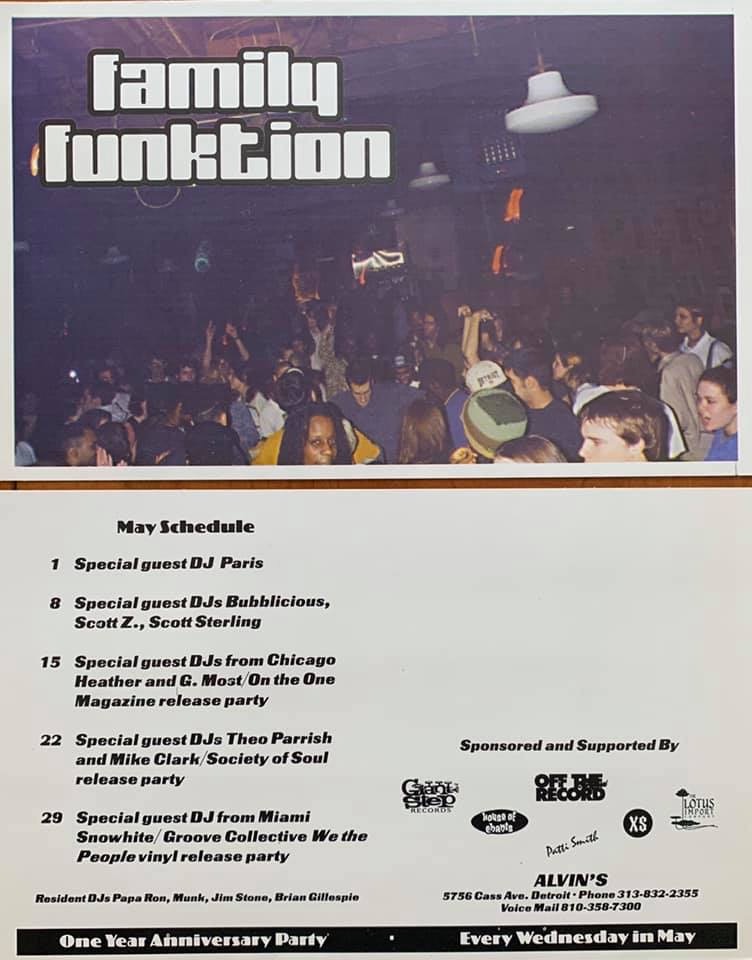

From 1995-1998, Stone helped organize, promote, and DJ as part of Family Funktion with Alvin “DJ Munk” Hill, Poppa Ron, and Brian Gillespie. The night brought in 300 to 400 people at times. Funktion, Stone argued, was loosely based on Giant Step, a party in New York that later became a record a label. Family Funktion which began at Alvin’s in the Cass Corridor (now Tony V’s.), was critical in bringing various scenes and personalities together during a time of underground musical experimentation. It was a time when genre boundaries were bending and Detroit’s true nature as a big city / small town came forward. You could love hip hop and dance at raves, be in a big guitar rock band and listen (and be inspired by) acid jazz. DJs like Theo Parrish, Matthew “Recloose” Chicoine (then DJ Bubblilcious), Scott Sterling, and Heather “DJ Heather” Robinson, would join the regular crew for release parties.

Drake Phifer, DJ, promoter and founder of Urban Organic, was just one of many Detroiters who were inspired by what Jim was doing during this period. “When I first moved back to Detroit in the mid-late nineties I was completely depressed and had every intention of moving back to Atlanta or going to DC. There were four things that kept me here. Dennis Archer being Mayor and saying that Detroit was on its way to being a “world class city,” an idea that I bought into, Korie Enyard’s Better Days events, Twingo’s Cafe opening on Cass Avenue, and Family Funktion. Family Funktion was the coolest vibe around and Jim at last brought all the folks I loved. Cooley’s Hotbox, Theo Parrish, Ursula Rucker… and so many great underground acts. It was Detroit music culture at its finest.”

“When I began Urban Organic in 2001, I would call Jim up at first and try to pick his brain for ideas and concepts. Jim had a great relationship with Giant Step in New York, who we viewed at the time as culture gods. My relationship with them was cool, but not like Jim’s. What made that so important is that things are not like they are now where artists can communicate directly with their audiences… they needed clearinghouses, and Giant Step was one major one for us. I got some of the love from Giant Step when it came to having artists tour through my shows, but Jim got all of the love! But he would always say, ‘Drake, your secret ace in the hole is the fact that you lived in Atlanta and were able to pull from that scene,’ and he was right… and I had never thought about it like that.”

Then aspiring music journalist now educator Diana Potts met Stone during this period when, in her own words via email, Jim and his cohort were exploring an “idea of a community driven by music” a “soulful backdrop for friendships to synergize.”

“Jim introduced me to countless bands and musicians. One of my random memories of Jim was that he always had a box of CD’s in his trunk from a new artist. Introductions to bands like Esthero and Zero 7 were because of Jim lugging around CD’s in his car.”

Potts continues: “I have so many memories of Jim, from runs to get ice cream in Ferndale to parties in Detroit to Miami Winter Music Conference and back. What resonates most about Jim Stone is that he always made me feel welcomed and loved as a human being. And that is the music he leaves with me.”

Via email, when we told him that Stone had died, DJ and producer Theo Parrish simply responded: “Damn.”

“Sad to hear this. Always had positive exchanges regarding the music with that guy…. My love and condolences to those who knew and loved him well. May we all carry health sanity and clarity with us as we lose these good people.”

[What a clip of Theo Parrish captured at Family Funktion via Youtube.]

Like similar genre-defying events like jean designer and promoter Maurice Malone’s Underground Nation parties earlier in the 1990s or the long running Three Floors of Fun at St. Andrews which allowed scenes to mix together by merely moving up and down a staircase, Family Funktion was like a great rent party put on in public, open to all. If Jim had done nothing else in his time in the scene, his legacy would have been impactful enough to be remembered by those that worked and performed with him during this period.

DJ, Promoter, and Advocate

The Movement Festival, then called Detroit Electronic Music Festival (DEMF), brought a new visibility to the scene and, along with the digital Internet revolution occurring simultaneously, changed the scene that Stone had known forever. In 2004, Stone described Detroit as a “weird and fickle city” with “regulars” — an audience that Stone had helped create the space for — dropping off.

But Stone continued. At home in both “Alternative” or “Lounge” events in local papers, he DJed art openings and brunches, opened for neo-soul and trip-hop parties that he promoted, and even in the occasional wedding (see photo above). But also shared himself and joined forces with the folk-electronic group The Twilight Babies.

[Watch “Forlorn” by The Twilight Babies via Youtube.]

Postlude

Jim Stone, like many participants within Detroit’s musical ecosystems, never thrived financially, even when work was available and dance floors full. In addition, over the last five years of his life, he suffered from physical and mental issues. In the final years, he stayed in group homes and was receiving State funds for disability. His speaking slowed making it difficult at times to communicate. He fell in and out of touch with friends.

Phifer reached out during this period. “I told him that it was lonely being out here doing shows by myself and that I needed him to get back in the game. He tried a few times, but the reality was that — and he admitted as much — he was burned out.”

However, even earlier this year, he had reached out to our network of allies and had made plans to get together. He seemed positive about the future and was speaking confidently about being able to find new work despite his struggles. But a stroke felled him. He was 54.

There has yet to be a national day of mourning set for the now over 175,000 that have been lost to COVID-19 this year. And of course, memorial events to others who happened to die this year will be delayed until it is safe to gather again. We here at DSC look forward to that time and celebrating Jim — and so many others — soon. But even without a large celebration Stone’s impact can be felt through the people he touched and the musical resonances he made possible. He helped co-create the sonic water we all swim in here in Detroit, from his first days as a teenage rock singer almost 40 years ago to his final DJ gigs this last decade. Honored or not, his impact continues.

Carleton wishes to thank: Dan Bell, John Briggs, Brian Gillespie, Susan Green, Kimberly Hackett, Matthew Heidmous, Alvin Hill, Jon Howard, Zack Knutson, Meredith Ledger Seller, Kito Jumanne-Marshall, Bob McCreedy, Nancy Mitchell, Theo Parrish, Drake Phifer, Steven Reaume, Poppa Ron, Diana Potts, Tim Price, Tim Retzloff, Heather Robinson, Mike Rubin, Kevin Saunderson, and Laura Simone.

You may also read Jim’s entry on Michigan LGBTQ Remember here.

Did you know Jim Stone? Or do you have corrections that we should make? If so, please leave a comment below or get in touch with us directly at info@detroitsound.org or 313-757-5082 and share a memory that we can include in future revisions of this piece or in the collection we are gathering to honor the legacy of Jim Stone and the scenes he touched. Thanks in advance.

Kito Jumanne-Marshall

Ahhh, Carleton. Well done. I can only imagine how difficult it must’ve been to compose this beautiful tribute to such a dear friend. Like all of us, I have so many fun memories (of hugs, kisses, and general sillies) but my favorite would be that, after Kenjji and I moved out of the D in ’05, Jim would regularly invite me to whatever party/concert was happening next. We had an infant at the time so travel was limited, but he and I would text and occasionally talk on the phone, especially if it was about a Tortured Soul show lol. He was 100% pure love all the time, and we sure did kiki as much as we could. I will miss him. I can’t believe how iconic this photo came to be, and I’m beyond humbled to have shared sacred moments with these two sweet souls let alone to have captured this moment. Love you, friend. Rest in peace, Jim & LaVell.

Colton Weatherston

Jim was a kind and generous man. Our circles of friendship in Detroit music overlapped a lot between 1998 and 2010. I remember those times being filled with creative people and Jim was always opening doors and making introductions. He made a tough world brighter. Let us give thanks for his example.

Bill Shuster

This article is so important in that it documents how Jim was in fact the linchpin that tied together many overlapping and unique scenes. This sprang from his unique intersectionality, kind demeanor, and he was infinitely sharing of his creativity, vision, and light. Jim introduced me to a lot of great music over the years. As my memory serves, it is also important to mention that Jim’s family was engaged and supportive. I’ll never forget Jim’s father helping me move my speaker cabinet into their basement, and then showing a lot of enthusiasm as we rolled out the hits of yesteryear like the Jim Stone-penned, neo-psych cut “Strobelight”. Good times. Still processing that he is no longer among us, but am comforted that his spirit indeed lives on in each of us.